Over the years, I’ve learned to ask myself two simple questions before I take any photograph: What is my subject, and what is the best way to showcase that subject? Subject refers to the main object or focus of the image; for instance, a person would be the main subject in a portrait, and the entire scene would be the subject of a landscape. What lens you use will help determine the look or “expression” of the subject and is a very important decision on how the final image will look.

How do I choose the right lens? I need to know my subject, what I want to highlight or focus on, and what I want to eliminate. If my subject is wildlife, I know that getting physically close can be difficult but I can get visually close with a long focal length lens of 200mm or more. If I’m shooting a scenic image where I want to capture the grandeur of the place, I’ll use a wide lens, generally from 15–35mm. Sporting events generally require long lenses to get into the action, but you also need faster shutter speeds to freeze the action, so you’ll want “fast glass,” which allows more light to reach the sensor (we’ll talk more about that in a bit). A portrait session will normally use lenses from 80–200mm, which give the best looks with the least amount of facial distortion.

Choosing the right lens, however, isn’t simply deciding what focal length to use to make the subject larger or smaller in the frame. Lenses not only have a function—letting light in and focusing it on the sensor—but they also have an effect on the look of the subject. It’s the understanding of this relationship that will enable the photographer to express an intended meaning. Let’s look at some examples.

Depth of Field

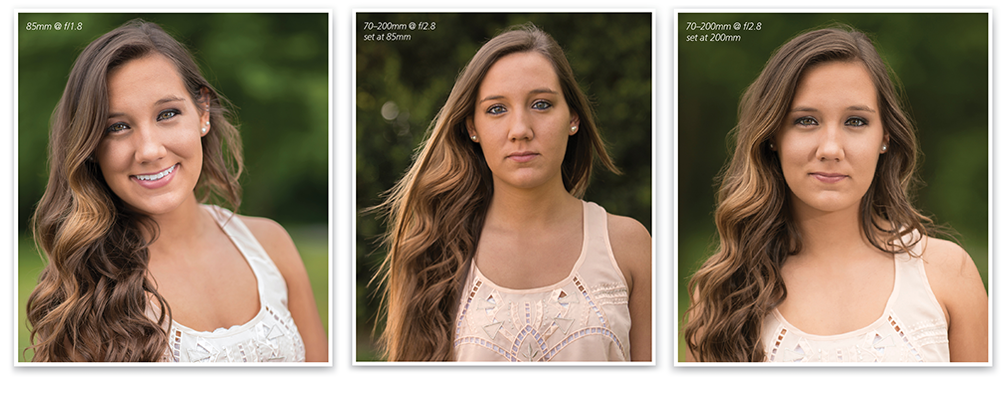

There will always be debate over image quality between zoom and prime lenses, but I’d like to stay with our theme of expression when deciding what lens to use in a given situation. In most cases, prime lenses are able to offer larger maximum apertures than zoom lenses. Since aperture and lens focal length are two major factors in controlling depth of field (DOF), it’s important for us to understand their relationship. The first image shown here was taken with an 85mm lens opened to an aperture of f/1.8. The second image was taken with a 70–200mm zoom lens set at 85mm. So our first thought is that they’ll look pretty close to identical; however, the maximum aperture for the zoom lens is f/2.8, giving the background a slightly different bokeh (or blurring). This degree and style of background blur is an effect that photographers might use to express their subject.

Focal length is also a factor in DOF, so let’s take that same 70–200mm lens out to 200mm and move back to get the same framing. As you can see in the bottom image, the longer focal length with the same lens offers a different background effect.

Angle of View and Lens Compression

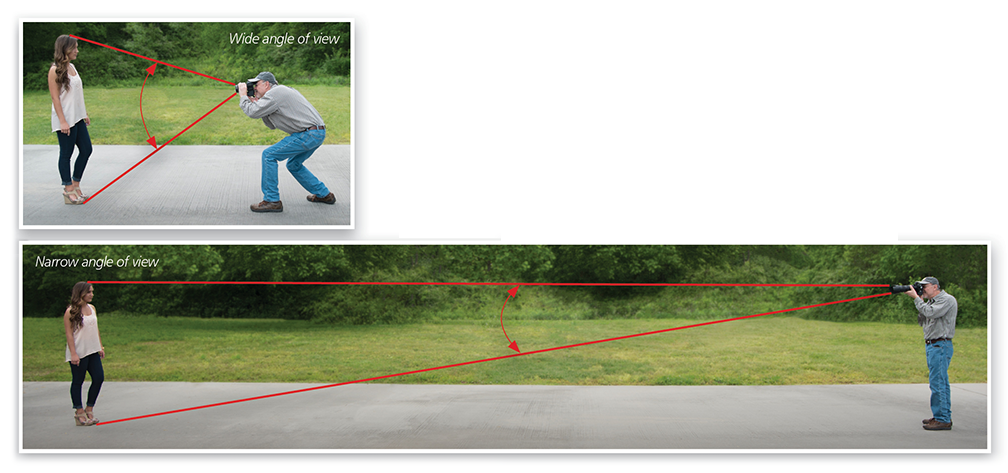

The combination of focal length and aperture causes another effect called “angle of view.” In terms of expression, angle of view controls how a viewer perceives depth in an image. These next two images illustrate the narrow angle of view of a telephoto lens compared to a wide lens. A narrow angle of view creates a look that’s compressed or flattened.

Compare the first image below, taken at a 200mm focal length, to the second image, which was taken at a focal length of 70mm. The subject in each image has remained relatively the same size, but notice the difference in the background elements. Because of the compression of the 200mm lens, the building—which is actually far away—appears to be right behind the subject and becomes a distraction. So you need to be aware that lens compression can either be your friend or foe according to how it affects the background.

Instead of trying to compress a scene, you may want to communicate a sense of distance or depth. The wide lens, with a wide angle of view, is great for this. This effect can be enhanced by introducing a strong foreground element that attracts the attention of the viewer. Generally, lenses with a focal length of 35mm and less are considered wide. Lenses 20mm and wider are considered super-wide and usually produce some type of distortion. Along with the ability to show depth, wide lenses express the expanse of a landscape because of the wider aspect ratio.

Aperture

The first image in the next example was taken with a 70–200mm lens with a fixed maximum aperture of f/2.8, while the second image was taken with a prime 300mm f/2.8 lens, which retails for several thousand dollars. In contrast, a 70–300mm lens with an aperture of f/4.5–5.6 can be purchased for around $200. At first glance, the price difference may make the purchasing decision a no-brainer; but staying with our theme, let’s make sure we understand the difference in effect.

Clearly in terms of focal length, the 70–300mm f/4.5–5.6 lens makes a very powerful and inexpensive option for photographing wildlife, action, or sporting events; however, the f/4.5–5.6 aperture numbers indicate that the lens is a variable aperture lens. This often confuses people, especially first-time lens buyers. Besides having a maximum aperture of only f/4.5, the maximum aperture is actually reduced to f/5.6 as you zoom.

The aperture is an adjustable opening in the rear of a lens that’s designed to control the amount of light reaching the image sensor. It works with small metal blades that mesh together to form this opening. In the same way your pupil closes or opens according to the amount of light entering your eye, the aperture is opened or closed in response to the light meter in your camera.

Remember that each function has an effect. More light reaching the sensor allows for a faster shutter speed, meaning you can capture faster-moving subjects without raising the ISO. It also affects which elements remain in focus both in front of and behind your subject. While a large aperture of f/2.8 lets in more light, its effect is a very shallow DOF, as demonstrated in this next image. In other words, elements in front of and behind the subject are out of focus. The small aperture of f/22 in the following image reduced the light reaching the sensor but allowed the foreground and background elements to remain in focus. All these adjustments can be quite a challenge for a beginning photographer. While controlling the DOF may be your primary goal, the exposure is also affected by your adjustment. This demands that you consider your shutter speed or ISO setting.

The numbers used to represent the aperture size can cause confusion, as they seem to be the opposite of what you’d think—for example, f/22 is a much smaller opening than f/2.8—and that’s because these numbers don’t represent diameter. They’re a function of the focal length divided by the diameter. The reason that we use f-numbers, rather than diameter, is so that f/22 on a 200mm lens lets in the same amount of light as f/22 on a 15mm lens.

With a zoom lens, the focal length is adjustable, so if the aperture remains the same, there will be an effective difference in the amount of light reaching the image sensor as the lens is zoomed. With these variable aperture lenses, there’s both a function change and an effect change as you zoom in and out. The opening size doesn’t change, but when you zoom in, the amount of light reaching the sensor is reduced as if the opening were smaller; and as you zoom out, it increases as if the opening were larger.

In contrast to variable aperture lenses, more expensive lenses provide large apertures regardless of focal length. This design requires larger lens elements, or “fast glass,” and is more expensive to manufacture. Since fast glass lets in more light, the photographer is able to use a faster shutter speed to stop action without raising ISO. This is greatly desired by professional sports photographers who require high-quality images in low-light situations.

Image Stabilization

When I was a much younger man learning photography in the 1970s, my mentor established a hard-and-fast rule that couldn’t be broken: When shooting without a tripod, never use a shutter speed slower than the reciprocal of your lens focal length. This rule was designed to prevent image blur caused by handholding the camera with slower shutter speeds.

To find the reciprocal of a number, you simply place a 1 above it. In other words, the reciprocal of 2 is 1/2. If we apply this rule to a lens with a focal length of 200mm, our minimum handheld shutter speed would be 1/200th of a second. Hand-held, a slower shutter speed than 1/200 would likely cause image blur. Keep in mind that this rule only applies to movement of the photographer and not the subject being photographed. Moving subjects may require much faster shutter speeds to achieve a sharp image.

Like many other rules, our modern world offers a challenge with image stabilization. Image stabilization is a mechanism that works to compensate for camera movement, enabling slower hand-held shutter speeds. Some manufacturers build image stabilization into the camera body, while others build it into their lenses.

An image-stabilized lens is designed to minimize camera shake caused by either the photographer or the base on which the photographer is positioned. It’s very useful when a tripod is impractical, or if the photographer is on a moving platform, such as a helicopter or vehicle. Image stabilization offers many advantages over the reciprocal rule; however, every function has an effect. Image stabilization in a lens uses a mechanically driven, floating lens element to compensate for camera movement. Most camera manufacturers recommend you switch image stabilization off when using a tripod or shooting above certain shutter speeds because the stabilizing device may actually produce image blur. Each photographer should try different settings and experiment to find what works best in each situation with their particular equipment.

As you can see, we have come full circle. If you know your intent and understand the effects of various lens choices, you’ll choose the lens that best expresses your subject. Unfortunately, this brings us to one more important consideration: Long focal length lenses with large apertures and image stabilization are expensive. Considering the cost and many options available, you must be sure you understand the function and effect of a lens before making a purchase. A good lens will outlast several camera bodies while also enabling you to express your subject in a unique way. Choose wisely!

This article originally published in the July/August issue of Photoshop User magazine.