“Okay, we’re only doing this once,” Patrick says, with obvious tension in his voice, over the thunderous roar of the waterfall. “We’ll have a safety boater below the falls in case something goes wrong.”

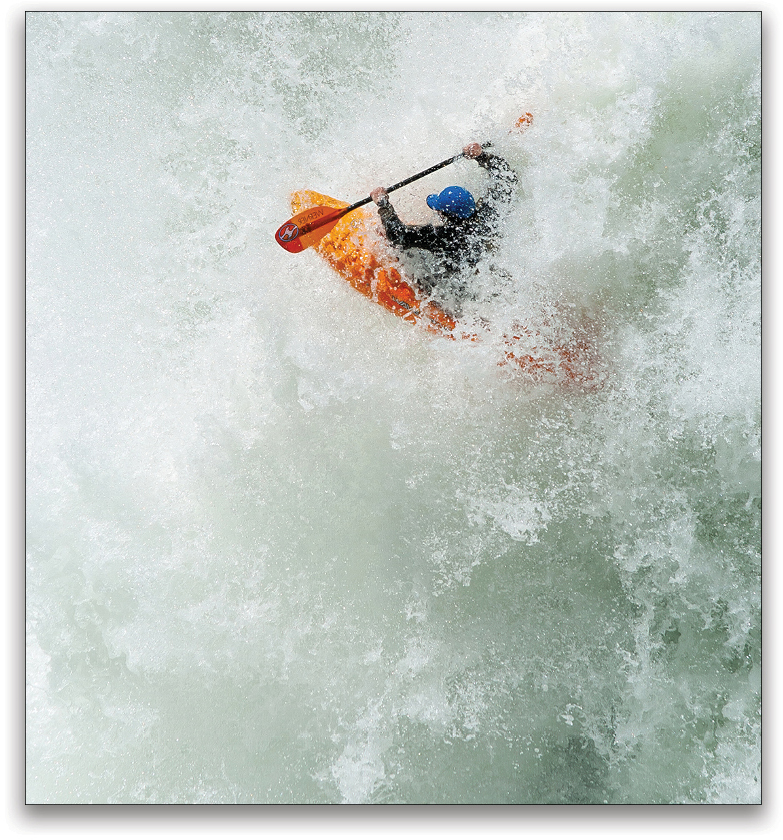

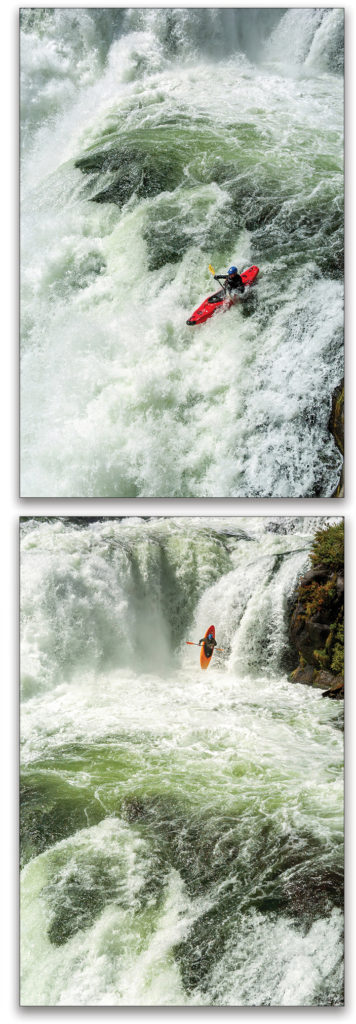

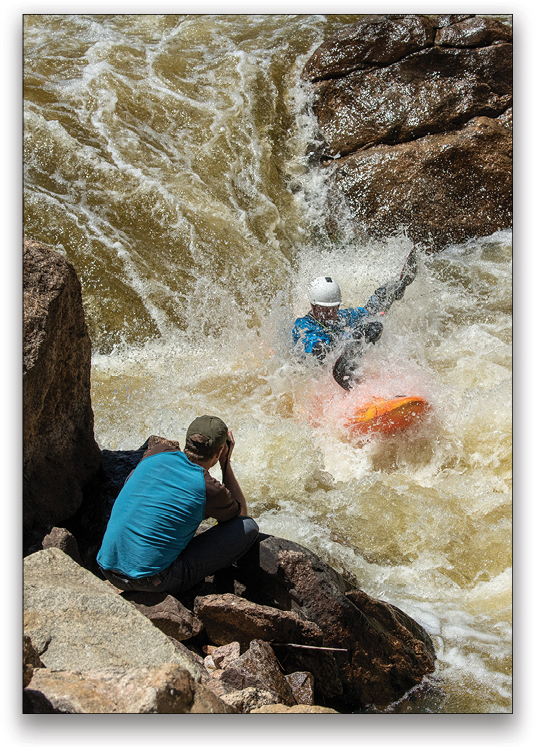

I’m not sure who’s more nervous, Patrick or me. I’m perched on a rock pinnacle, tied to a rope, looking down into a maelstrom of whitewater and mist. I’m photographing some friends who want to paddle off Lower Mesa Falls, a 65′ waterfall in Idaho. Yesterday, in Colorado, we were talking about summer plans when we heard conditions were perfect to run Lower Mesa Falls. On a complete whim, we loaded up our trucks, threw kayaks on top, and drove nine hours to this waterfall. Peering at the massive waterfall, I’m not so sure this spontaneous idea is a good one. Maybe a few too many beers were involved in this decision. But Patrick is totally focused, and this run is on his kayaking bucket list.

I can’t mess up these photos. I have to be sure my exposure, shutter speed, and composition are perfect. Patrick raises his paddle to signal he’s going for it. Time seems to slow down as he approaches the lip. I’m pressing my camera so hard into my face that it will leave an imprint for days. My shutter blazes away at 10 fps as Patrick floats off the lip and rides a whitewater curtain into the turbulent misty chasm below. And then he disappears. I keep on shooting, even though all I see is whitewater froth in my viewfinder. Suddenly, his red boat emerges from the mist, and Patrick is doing a rodeo twirl with his paddle. A perfect run, and he is psyched! This is a photo shoot I’ll never forget.

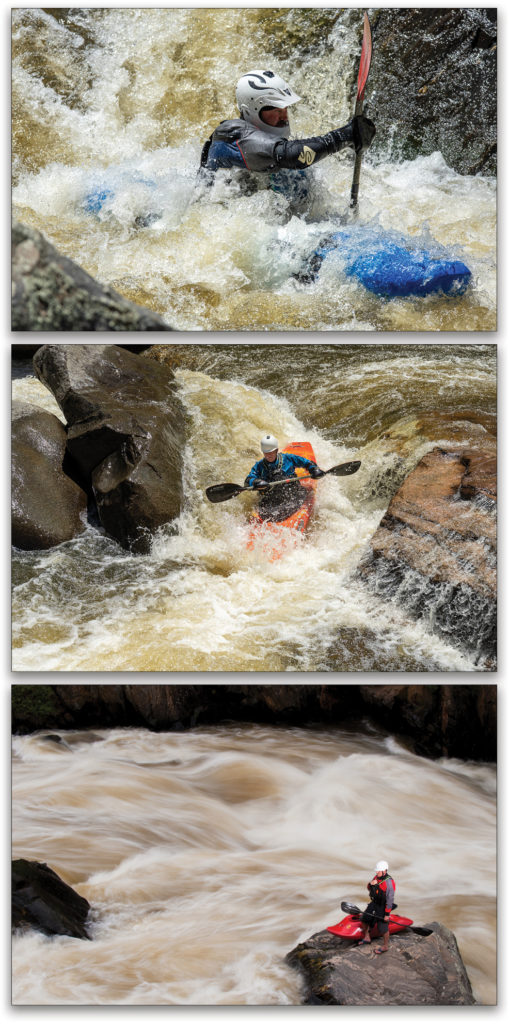

Whitewater paddling offers photographers incredible action-photography moments. Photographing rafters and kayakers running big rapids captures a beautiful mix of adrenaline, emotion, and risk in one captivating image. You don’t have to be a whitewater boater to appreciate a stunning kayaking image.

Photograph Your Local River or Whitewater Park

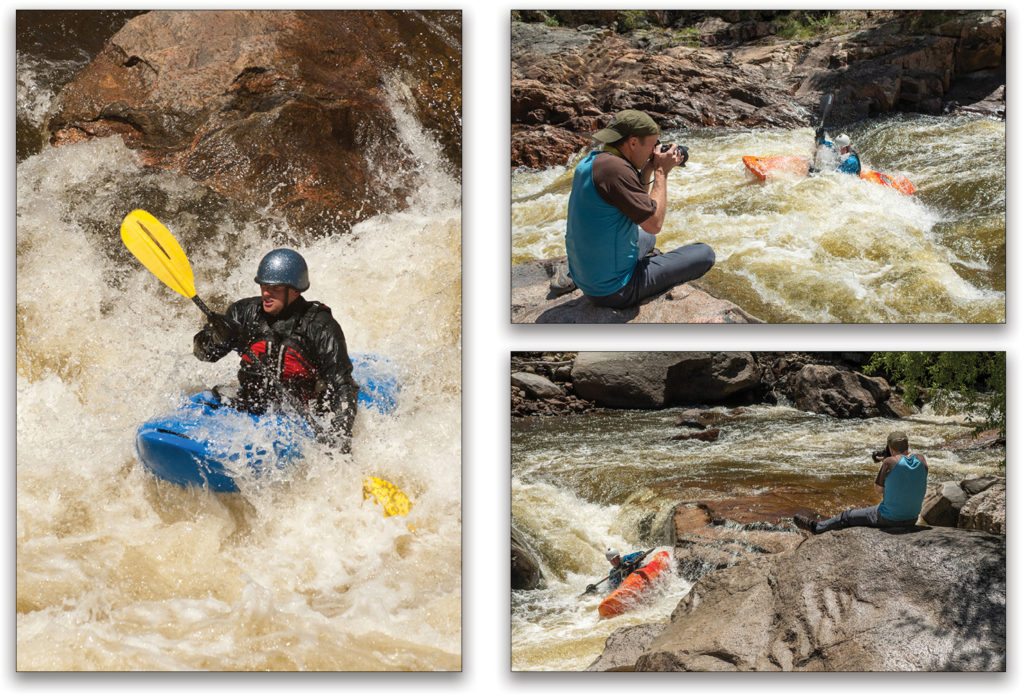

Okay, I realize many photographers might be saying, “I’m not dangling off a rope to photograph some crazy guy paddling off a waterfall.” But here’s the good news: You don’t have to be in a kayak (or hanging off a cliff) to capture a great image. You can be dry and comfortable on the riverbank while a kayaker paddles through a churning rapid only 20′ away.

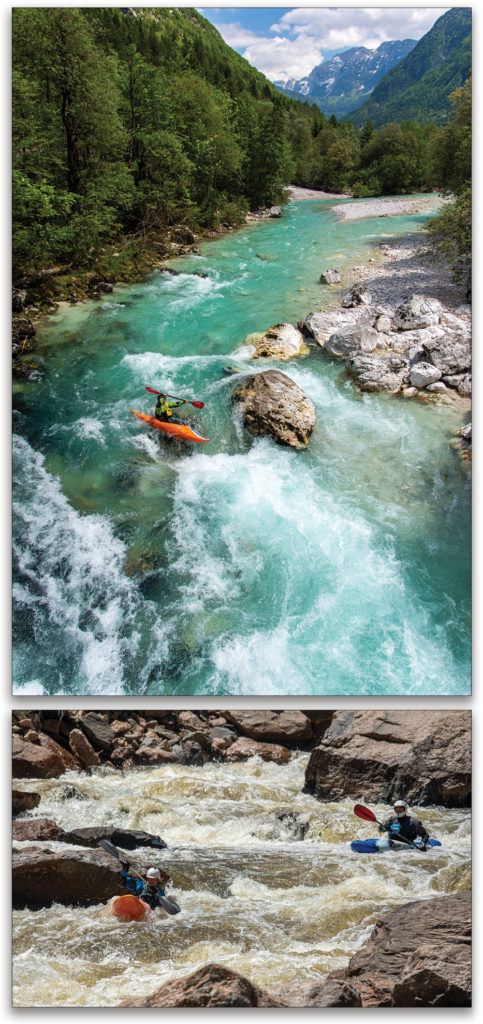

There are fantastic rivers all across the U.S., and many have easy access for photographers. Research your local rafting companies and see what stretch of river they run. Many rivers flow right along roads, and you can find great shooting locations right beside your car.

I live in Colorado, along the Cache La Poudre River, and my town embraced another popular trend in river running last winter by building a whitewater park in downtown Fort Collins. Whitewater parks are popping up in many urban areas in the U.S. These parks, which offer an economic boost to the area, provide even easier photography access to whitewater boating. Paddlers will spend hours surfing big waves and performing tricks right beside paved paths with benches. After photographing the action for a few hours, you can grab dinner right beside the river.

Getting the Shot

With such easy access for photographing whitewater paddling, the challenge is less about finding the action and more about how to capture it. To start, think fast shutter speeds—really fast shutter speeds. I like to photograph whitewater action at 1/2000 and faster. Water droplets and spray will be flying through your shot, and nothing is worse than blurry water when you’re trying to create tension in the image. “Diamond” water droplets require fast shutter speeds; so if the light is low, crank up your ISO to allow fast shutter speeds.

Next, take a few test shots where the boater will paddle. Dynamic, breaking white waves can confuse your camera meter. You want to expose for the highlights, since a lot of your image may have white-capped waves. Set your motor drive as fast as it will go, so you don’t miss a frame of the action. I normally use a single-point autofocus pattern and do my best to put it right on the paddler’s face. Another option is to pre-focus on a drop the paddler will go through. Also, group patterns can be confused by nearby waves.

I like to use continuous servo autofocus mode to track the boater as he paddles through the scene. I also look through my viewfinder with both eyes open. This allows me to see when the kayaker enters the scene, and be ready for the critical moment when he’s in my viewfinder.

What about composition? I normally take two different approaches. First, I may find a distant spot from the action and focus on an environmental shot. I find an overlook where I can shoot down on the winding river and brightly colored boaters. These compositions provide a nice contrast to tight action shots.

But my favorite images are documenting whitewater action. Carefully consider your position to the whitewater. For whitewater “headshots,” I love being at the river level, especially if the waves are big. The paddler may disappear as he paddles through the rapid, but images of a paddler crashing through the waves will be stunning.

If you move to a position slightly above the river, you’ll capture more middle ground and longer stretches of the river. It’s also easier to see the paddler and maintain focus. One important thing to watch is the kayaker’s paddle position. Things happen fast, and many images will have the paddle blocking the boater’s face. Shoot as many frames as possible to improve your odds of the perfect paddle position.

Portraits on the River

If you’re a portrait photographer, whitewater gives you an amazing opportunity for an environmental portrait. You can position a kayaker—or a supermodel—in front of a frothing rapid to create a striking portrait. A big decision you’ll have to make is what shutter speed to use. I start by taking numerous test shots, looking at the texture and motion in the river. I often photograph using a slow shutter speed (around 1/2-second) to record motion in the river behind my subject.

I like to use flash, as well. Using flash allows me to underexpose the background and river, creating more drama and mood in the final shot. Just be careful using lights near the water! If you really want to produce a moody shot, set your white balance to Incandescent and use full-CTO gels on your lights. The gels will keep your flash at a neutral daylight white balance while the background will be dark blue.

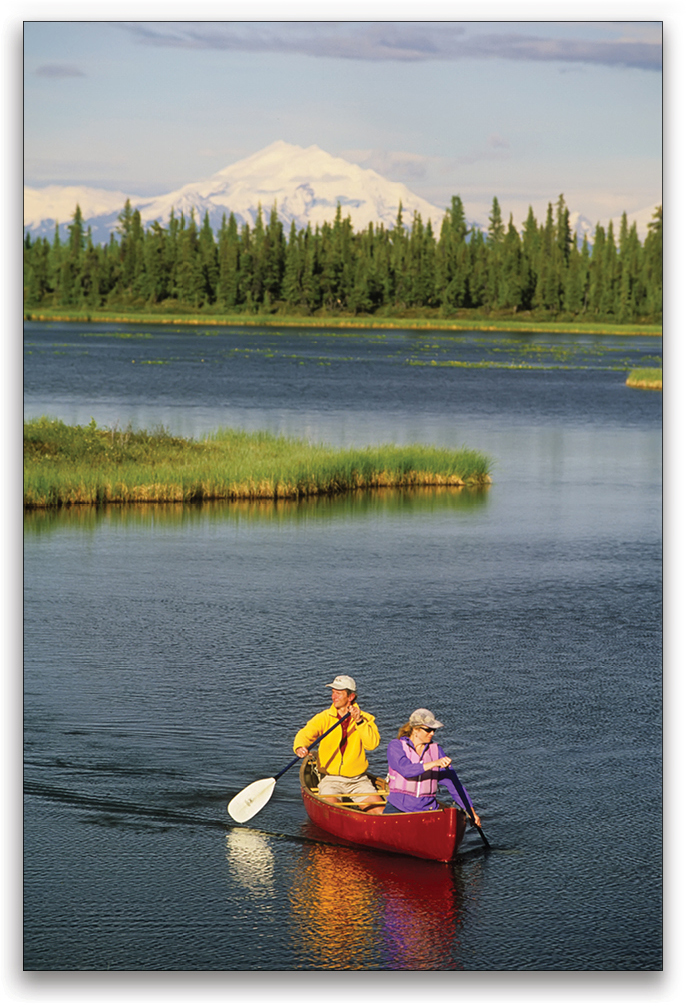

Take Your Own Boat Out

If you’re not interested in whitewater action, there’s another great image opportunity that everyone can do: photograph canoeing. Any lake will do, and many locations rent canoes. You don’t have to be an expert paddler, just make sure you wear a life jacket when you go for a paddle. Or photograph canoeing from the shore. It’s hard to beat a colorful fall scene bordering a lake with a canoe in it. Many national parks have lakes and canoe rentals, so consider this subject in addition to your landscape and wildlife photography goals.

Try a Special Technique

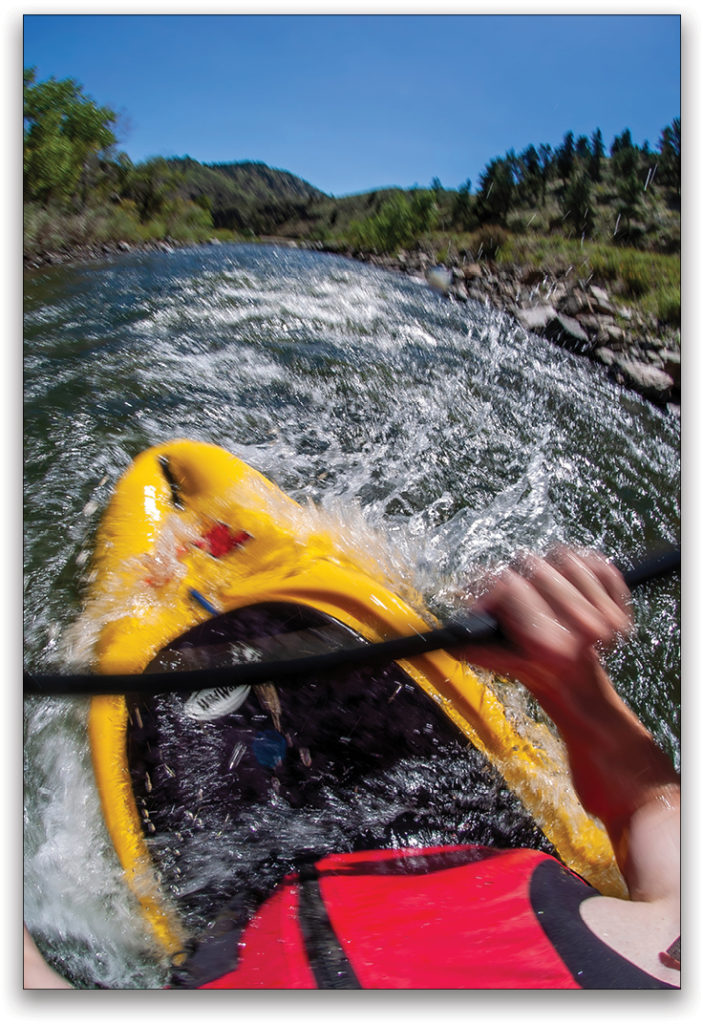

There are a few special techniques you might consider to spice up your paddling images. One of my favorites is a POV, or point-of-view, image. You can use a small action camera, such as a GoPro on a head strap, and paddle down the river solo or with someone in front (like in a canoe). This view really shows the viewer what it’s like to be paddling in the boat. For another angle, try attaching the GoPro to the end of your paddle.

I have an old climbing helmet with a tripod head mounted to it. I can attach my Nikon Z7 with a 14–30mm lens to this and paddle away. To trigger the camera, I set my self-timer to take nine images with a 3-second delay between shots. I just reach up and hit the shutter button, and start paddling.

You can also use your GoPro underwater or with a split view, above and below the water. Water-level views really catch a viewer’s attention, but take a lot of trial and error to get a great shot. Another approach is using a large underwater housing with your DSLR. Having a larger port and better viewfinder will dramatically improve your ratio of good images, but be prepared to spend a lot of money on the underwater housing.

Colorado has had a record snowfall this winter; even now, with summer starting, the mountains are still white. The rivers are going to run high and long this year. I can’t wait, because another season of whitewater action photography is here!

This article originally published in Issue 52 of Lightroom Magazine.