It’s hard to keep up with all the new technology in the photo industry. Almost every month there’s a new camera, flash, lens, program, or app that rocks the photo world. It’s an exciting time to be a photographer, and image-making is more popular than ever. I start my morning with a cup of black coffee and scan various photo websites looking for new, exciting announcements.

When Nikon introduced the SB-5000 eary 2016, I almost spilled my coffee. The speedlight I was dreaming about had arrived. Most importantly, the SB-5000 used a radio signal instead of an optical signal. This meant I didn’t need line-of-sight to trigger the light, and I could fire my flashes almost 100’ away. Combined with faster recycling, more power, and a built-in cooling fan, this flash wasn’t just a bump in features; it was a speedlight overhaul. And Nikon wasn’t the only company to improve their speedlights. Canon and others had introduced radio-controlled speedlights.

With these new speedlight capabilities, I needed to put the SB-5000 to the test. I wanted to see how well the new radio signal worked. How far could I trigger the flash? How many flashes could I get before the batteries started to struggle? To get some answers, I loaded up my trailer and headed to Great Sand Dunes National Park in southern Colorado.

Scout The Location

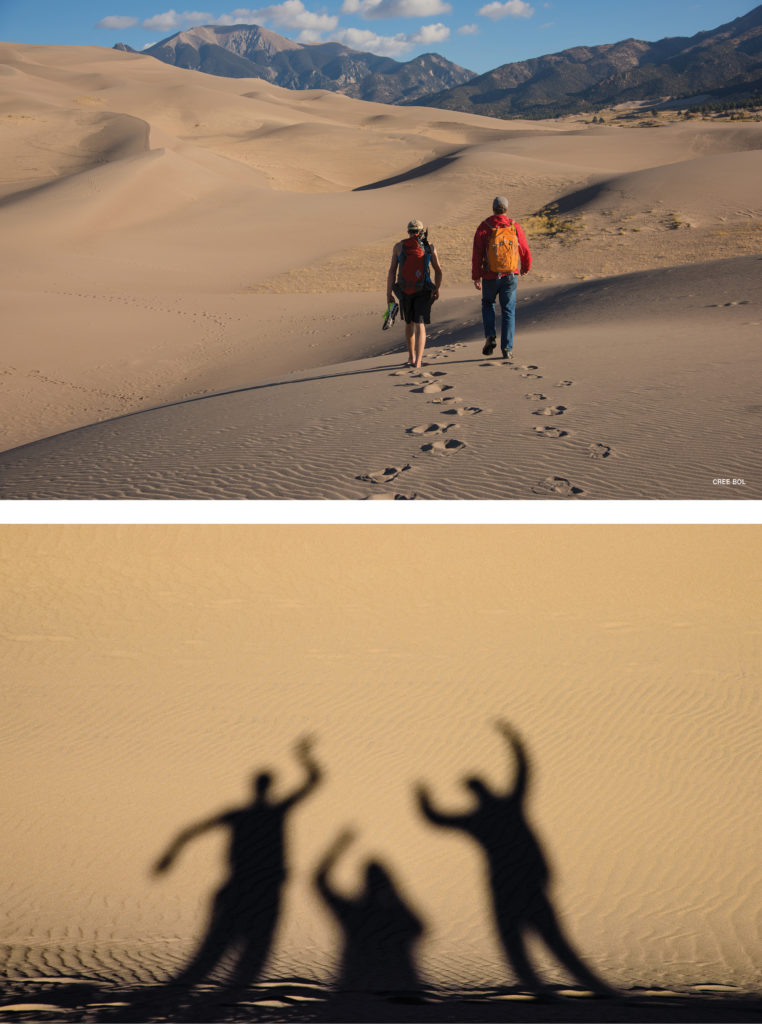

Or in this case, be overwhelmed by the location! These dunes stretch for miles, and the largest dunes top out at 750’. Imagine walking on the soft sand at the beach, except instead of being flat, you’re going up a very steep hill at 8,000’. I didn’t need to climb the tallest dune for my shot, but I was dazzled at the massive scale of the dunes. I brought my family along for this adventure. My wife is also a photographer, and my teenage son, Skyler, is a nationally ranked high school athlete. Since he trains constantly, Skyler makes a great athletic subject for outdoor images. This was going to be a family affair.

The Long-Distance Hiking Shot

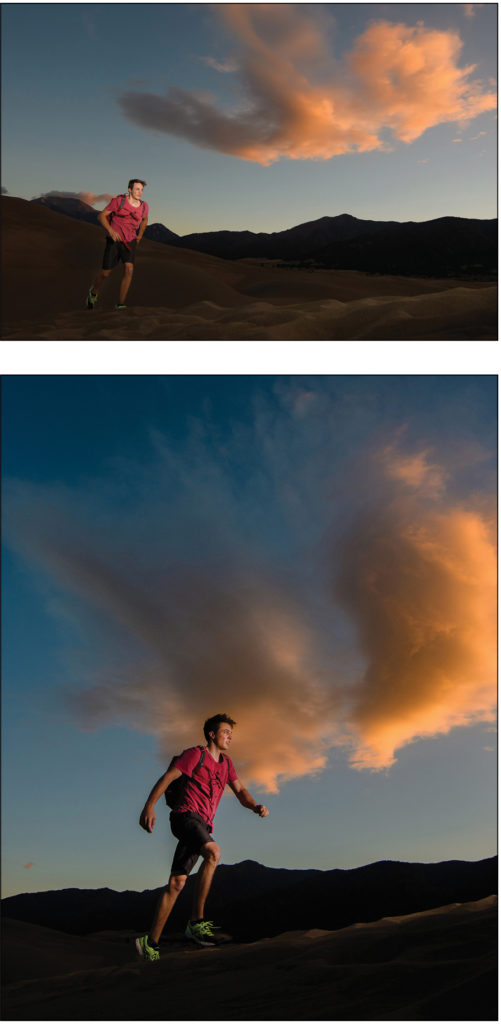

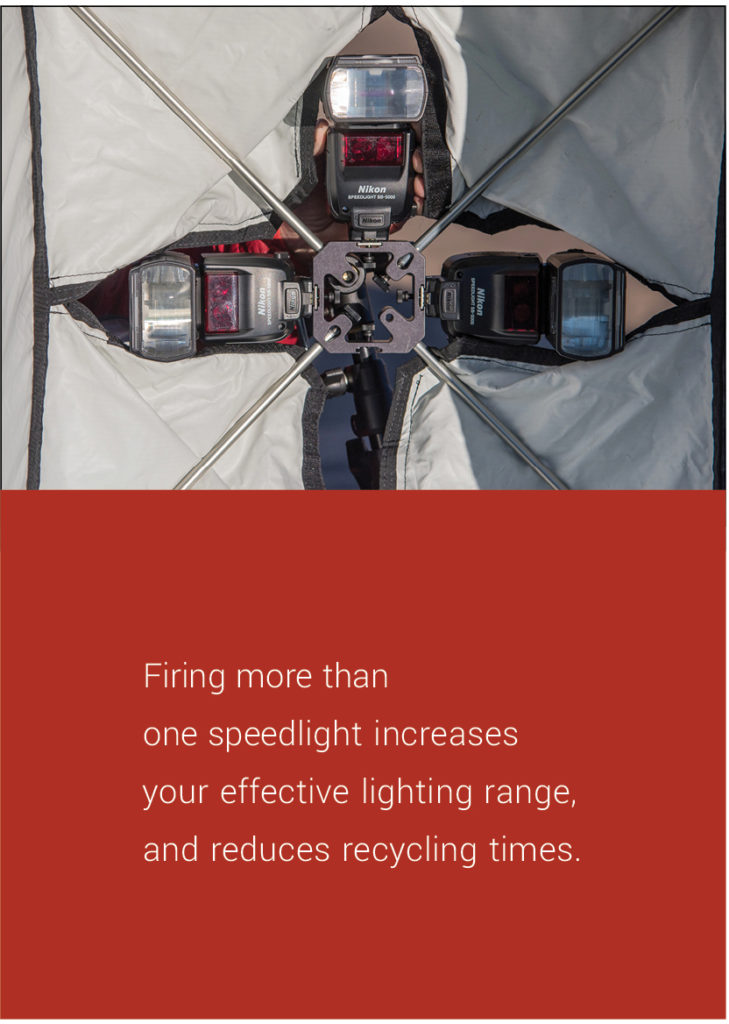

One powerful graphic element of sand dunes is the narrow ridges that crisscross the dunes. Almost any ridge will make a great landscape photo, and adding a hiker adds scale and perspective to the vastness of the environment. Under the stars in the chilly predawn darkness, we hiked by headlamp until we were surrounded by mountains of sand, and found a curving ridge that Skyler could run along. To light him, we placed a small light stand in the sand with a Lastolite Triflash bracket on top. This bracket holds three speedlights for plenty of power.

Using a Nikon D500 and a wide-angle lens, I was able to include the distant ridges and mountains behind Skyler for a dramatic background. But would the flashes fire with the stand behind me (not line-of-sight)?

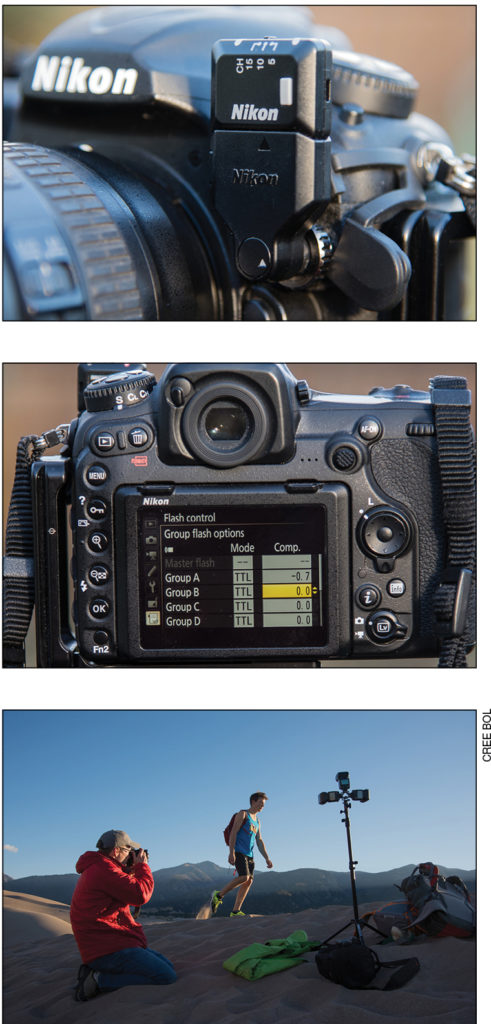

I attached the new Nikon WR-R10 Wireless Remote Controller to the camera’s 10-pin terminal using the WR-A10 Wireless Remote Adapter. One big difference from the optical SU-800 transmitter is that the WR-R10 doesn’t require a separate battery. Instead, it runs off the camera battery. Fewer batteries are a good thing. Also, this transmitter is so small that you barely notice it’s on your camera. To adjust power settings of the flash groups, you use a commander screen on the camera LCD. The radio receiver is built into the SB-5000, so no extra piece of gear is needed.

I took the first image, and the flashes fired right on cue. Shot after shot, the flashes just kept firing. I was getting a little giddy at how well this signal worked. The clouds were turning orange as the sun rose, and the speedlight added punch to the shot.

I asked Skyler to run to a distant ridge and set up the SB-5000. How far could he go before the signal failed. Back and back he went until at about 300’ the signal finally stopped triggering the flash. This was three times the distance Nikon states the system will work. How often will you shoot a football field away from your subject? Not often, but you have the ability now.

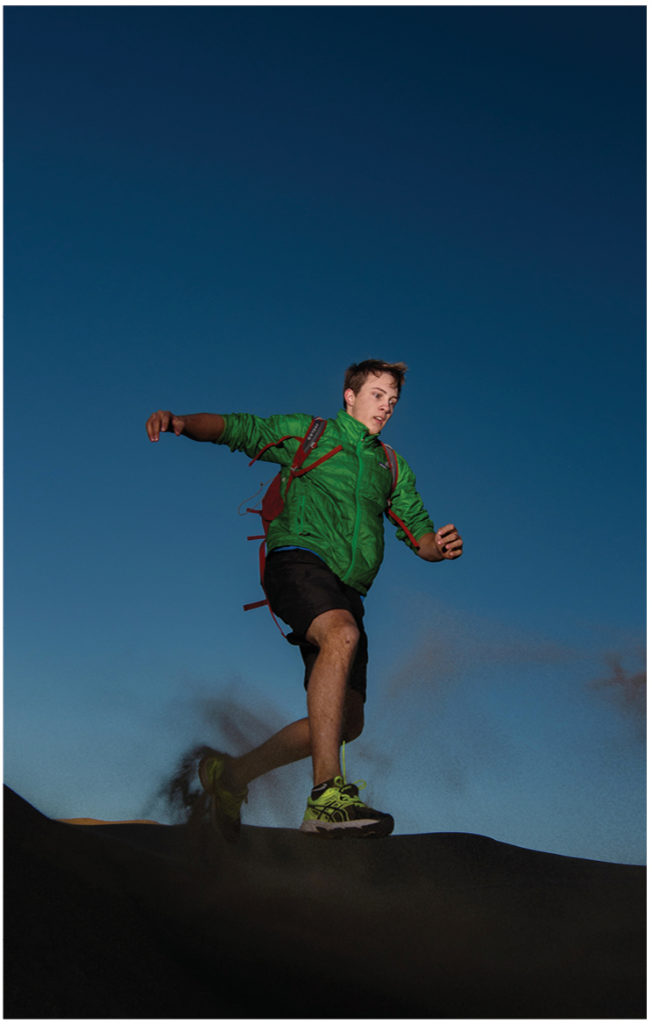

The Action Shot

Next up on my shot list was an action shot. I had heard rumors that the SB-5000 could shoot two to three frames in rapid succession. That meant instead of capturing one lit image in an action sequence, I might be able to get two or three. To test this idea, I moved off the ridge below Skyler. He’d be running along the ridge kicking sand, and I wanted to capture as many frames as I could with each pass.

I decided to use a 20” FourSquare softbox for travel portraits, I needed a softbox that could mount multiple flashes for this shot. The FourSquare box allows up to four speedlights to be attached, which would be necessary if I was shooting in high-speed sync (at shutter speeds faster than 1/250). In high-speed sync mode, speedlights use a lightning-fast strobic mode to ensure the subject is evenly lit using very fast shutter speeds.

Another radio control advantage became obvious. When I mounted the SB-5000s onto the FourSquare bracket, I didn’t have to worry which way the sensor was oriented. These flashes were going to fire no matter what their position in the softbox. Previously, using optical controlled speedlights, I had to use special brackets to ensure the sensor was aimed at the transmitter.

I took the front diffusion panel off the softbox to increase the power of the speedlights. I didn’t need soft light as much as focused light. The FourSquare does a great job of creating a beam of edgy light that can be aimed where you want it in your image. Skyler jumped off the dune for the first shot, and I fired my D500 at 7 frames per second (FPS). To my surprise not only was the first shot nicely lit, but so was the second image. This really shocked me. It’s hard to imagine these small flashes recycling quickly enough to shoot two consecutive frames at fast frame rates, but they did. I’ve never seen speedlight performance like this before. I shot numerous fast sequences where two or more of the images were nicely lit.

The Cross-Lit Sand Dune Runner

So far, I was a believer in the new radio-controlled speedlights. Weak and inconsistent signals were a thing of the past. My speedlights had fired every single time without missing a shot. They hadn’t overheated, and my rechargeable Eneloop batteries were still going strong. The action shots of Skyler looked great but I wanted to add a flash behind him to create cross lighting. The background light would help separate him from the sky, and add contrast to the shot. We placed an SB-5000 behind Skyler out of sight from the camera. We zoomed the flash head to 200mm to create a narrow beam of flash—we needed to illuminate Skyler, not the entire sand dune. I set my flashes in the softbox to group A, and my background accent light to Group B.

I’d been using TTL flash mode all day and getting great results. If I find TTL mode producing inconsistent output, I’ll switch to Manual mode. But one benefit of TTL mode is the ability to expose correctly for moving subjects. Skyler’s position changed almost every shot as he hiked through the image. But since I was shooting in TTL mode I didn’t have to worry about it. Using Manual mode, I’d have to shoot with Skyler in the exact spot each time for proper exposure.

Where to Go Next?

My SB-5000s were living up to all of my expectations. New images were possible using the radio signal, and the consistent firing was impressive. I shoot a lot of travel photography, and the ability to light a window or room from the inside while shooting from the outside would be terrific. The rapid-sequence flash firing was unexpected, and got me thinking about other action sports image possibilities.

The new Nikon and Canon radio-controlled speedlights aren’t cheap. At around $600 for one speedlight, some photographers may look at other options. But these flashes aren’t like speedlights of the past. More power, faster recycling, no overheating, and radio control make these a powerful lighting solution. And you can’t beat the weight. Hiking up that last massive sand dune during our shoot wore me out. But it wasn’t my lighting gear slowing me down. The shifting sand below my feet reminded me of a hamster on a treadmill. But you gotta do what you gotta do to get the shot.

Great Sand Dunes NP.

ALL IMAGES BY TOM BOL EXCEPT WHERE NOTED

This article originally published in Lightroom Magazine, Issue 26.